Presented by Arch Grants

Bioscience Startup Founders: Expect Bumps in the Road From Academic to Entrepreneur

Scientists entering the workforce are highly trained in their respective disciplines, but the academic world doesn't always prepare them for entrepreneurship. Two Arch Grants Recipients share how they learned to sell their science to potential investors and partners.

After receiving his Ph.D. in biomedical sciences, Christian Harding embarked on a post-doc fellowship that soon evolved into VaxNewMo, a biotech company developing antibacterial vaccines. Although his new company was built around his core expertise, Harding soon found that the skills that got him through university wouldn’t benefit him in business.

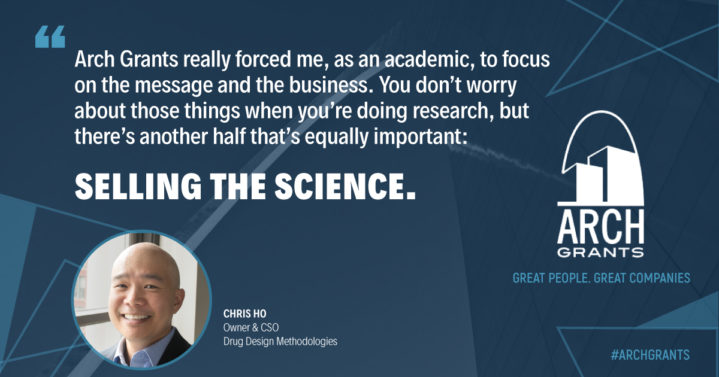

Chris Ho, founder and CEO of Drug Design Methodologies, shared a similar experience. Despite years of research in biophysics, he struggled to translate his densely technical work on the biophysics of pharmaceutical drugs into an appealing concept for the average investor.

These two scientists eventually found their footing in the startup world. Beyond mastering their field, they’ve mastered the abilities needed to define a business model and scale a company – culminating in both companies receiving an Arch Grant in 2017.

Just Get Started

The best strategy for any aspiring bioscience entrepreneur is to simply take chances.

“We were looking to get an SBIR [Small Business Innovation Research] Grant, but only had four weeks to write it, which is hardly any time,” commented Harding on the early days of VaxNewMo. “We weren’t sure we could get it done, but with a lot of help, we managed to get the thing written and submitted. And then we got the grant.”

For Ho, the “go-for-it moment” in founding Drug Design Methodologies was the turning point of his career. “I was an MD/PhD by training, and had to make a big decision about whether to go into medicine or stay in research,” Ho said.

“I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, so I took two years off to decide. At this time, every drug company I’d ever worked with said they’d support me if I wanted to start a company. So that was my big epiphany that I should be developing drugs instead of prescribing them.”

Neither scientist would have become a founder without putting the years of research under their belts. But they also wouldn’t have started companies without jumping in headfirst.

Even Good Ideas Don’t Sell Themselves

Most of Ho’s research at Drug Design Methodologies is highly technical, using quantum mechanics and other biophysical techniques to optimize the way that drugs bind to their targets within the body. As soon as he started pitching potential investors, he discovered that his core ideas didn’t necessarily speak for themselves.

Reflecting on his own journey from scientist to startup, Ho says, “[scientists] tend to take a meandering path [in academia], because science is never cut and dry—you never know it’s going to work.” In business, he counters, “you’re forced to focus and prioritize.”

Understanding what opportunities to prioritize, how to address your audience, and how to share it with the world could seem like “dumbing down” but it will help you bridge the gap between the academic and business environment.

“[Arch Grants] really forced me, as an academic, to focus on the message and the business.” Ho said. “You don’t worry about those things when you’re doing research; you’re always just trying to solve the problem in front of you. But there’s another half that’s equally important: selling the science—selling the drug.”

Whenever Ho started addressing the science behind his work, he began to lose the attention of his audience, who wanted to focus on the fundamental mechanics of his business. It wasn’t until he started pitching for an Arch Grant that he realized he needed to make a change.

“Focus on what’s really important in a business pitch: stop talking like an academic, and prioritize from a business standpoint.”

Tell A Strong Story

Although there are some similarities between giving a talk and making a pitch, you’ll need to change your approach when conveying ideas to potential investors.

“I’d never pitched before starting VaxNewMo,” Harding said. “I’d done presentations in science, and I’d given talks, but those are really different than pitching.”

As Harding learned the hard way, pitching isn’t a skill you learn in a lab. It wasn’t what he said so much as how he said it.

“Telling a story—really selling a story,” Harding stresses. “That’s what’s important. If you start going into the details, you’re going to lose the investors’ attention.”

Ask For Help When You Don’t Have the Answers

Since establishing VaxNewMo, Harding strongly encourages fellow entrepreneurs to go out on a limb and ask for help whenever they need it.

Simply reaching out over email can forge a deeply productive connection with an experienced mentor. Someone who can guide new founders through the inevitable trials and tribulations that any emerging startup will encounter.

In Harding’s case, that mentor was former Arch Grant Recipient, Harry Arader, now Director of Entrepreneur Development at BioGenerator, an early-stage bioscience startup incubator.

From helping perfect his Arch Grants pitch to simply introducing Harding to the industry contacts needed to scale VaxNewMo’s business, Arader has been “the biggest guy on the soapbox,” says the young entrepreneur.

“Don’t be afraid to ask for guidance,” he advised. “Don’t abuse people’s generosity, but do ask them for help, and the world will help you.”