Disrupting Aerospace Through Cubesats with Michael Swartwout

As the space industry enjoys a renaissance, entry-level employees might have already designed and operated their own satellites. Michael Swartwout, co-director of Parks College of Engineering’s Space Systems Research Laboratory, trains Saint Louis University students to launch their own spacecraft using the Cubesat platform. Swartwout is using miniaturization and collaborative techniques to help more people gain experience in space, at a lower cost than ever before.

What are Cubesats?

The Cubesat class is based on modules about 4 inches in each direction. Cubesats fit into a standardized launch container, which allows them to fly on every rocket used in the world. Because of this, more Cubesats are put into orbit each year than all other payloads combined.

What is different about space today than when you were a student?

Ten years ago there was a group of NSF and NASA people who saw opportunities for university use of space. With a standard deployment mechanism for all rockets to carry Cubesats, we now have simple missions that can go up in 2 ½ years rather than the 7 years it used to take. As a result, students and new employees can manage a full mission before they get assigned to a billion dollar program.

What are sample Cubesat missions?

There is single-instrument science, looking at Earth or the radiation belts or the interaction of Earth and Sun. You never used to be able to do your own simple mission and now you can. Historically, there’s also been a lot of risk with flying new components on a mission—it’s been impossible to test things in complex systems before launching.

With Cubesats we can test components separately as they’re developed, which is much faster and better for innovation. Then there is big data. Companies like PlanetLabs are developing the ability to image the entire Earth every day at 1 meter resolution with these low-cost Cubesats.

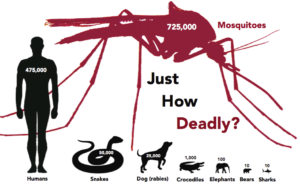

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 showed us that there are a lot of places, like the southern Indian Ocean, with very little reconnaissance coverage. In contrast, with their fleet of low-cost and quicker-to- develop-and-launch Cubesats, PlanetLabs will be able to actually see things like the daily movement and activity of all the world’s oil tankers wherever they go to allow people to predict oil availability.

Tell us about the picture you sent for use with this story—what’s interesting to you about it?

That’s me in red with the SLU student team for Argus. It was a joint mission with Vanderbilt University to improve our ability to predict how well modern electronics will work in the space environment. Argus itself is in the middle of the photo, so you get a sense of how small a student satellite can be and still do important research. Unfortunately, Argus was lost last month due to a rocket failure. The photo was taken back in September, so all of those students are still at SLU. A large fraction of them are actively seeking jobs in the space industry after graduation, at a range of large contractors and small startups.

Any thoughts on how your students fit into the local innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem?

When I was watching the first docking of the Dragon supply craft with the International Space Station by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, the narrator on the video feed was a familiar voice, a former student. She was the console operator for this important mission. I’ve since heard she is getting weary of the grind that working at SpaceX can be. She’s heard enough about the startup ecosystem back here in St. Louis to be exploring a move to work in the startup space here.

Imagine you spend a long flight with some amazing people—who are they and what do you talk about?

Teddy Roosevelt, he defies categories and fascinates me. John Marshall, who served with George Washington in Valley Forge, a delegate to the constitutional convention, and Supreme Court Justice for all these landmark cases at the formation of our country. Also Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, because just personally and professionally I want to understand their long games—why are they doing what they’re doing? When Bezos salvaged forty year-old Saturn V rockets from the ocean to reverse engineer them, it tells me he’s up to something interesting.

What current problem would you like to solve?

I think there’s a really straightforward way to get small satellites to transform or reconfigure once in orbit. For example, New Horizons collected amazing data on one side of Pluto. What if you could deploy sensors and get them back to see the other side? I’d love to work on demonstrating those kinds of capabilities.

What’s tough in what you do and what do you do about it?

Space has a lot of potential for hard stuff. Lots of stuff fails completely outside your control. It takes a strong will and a stout heart.

The first satellite we ever did here at SLU, Copper, was never heard from after launch. You look at what could do better next time, and you go forward. Teddy Roosevelt had a great quote about how the credit belongs to the one risking failure—you have to find the good in trying, getting invested and caring about things even if they don’t work out. The benefits of the process exceed the risks.