Presented by for Trackbill

What Does Economic Complexity Mean? And Who Cares?

In my previous article, on the Bioscience Labor Market Analysis in St. Louis, I explained the regional economic development complications caused by "overspecialization", and promised to provide a brief explainer on the issues of economic complexity in general.

So... Here's why questions of economic complexity are relevant to the St. Louis region.

"Increasing a region’s or country’s economic complexity — by making products of high complexity — is associated with increasing incomes and affluence.

Countries whose economic complexity is greater than [expected] tend to grow faster than those that are “too rich” for their current level of economic complexity."

Writing by Mike Fabrizi. Mike Fabrizi was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. An expat for 30 years to the Washington, DC area, he recently retired from a career including long stints with The MITRE Corporation, of McLean, Virginia, and The Aerospace Corporation, of El Segundo, California. Mike’s professional interests include complexity and complex adaptive systems, economic complexity, cities, and regenerative agriculture. He looks for ways to bridge the urban-rural divide, and likes to emphasize that which we share in common, not that which divides us. *Most* people everywhere are good. Give them half a chance and the goodness manifests itself. Mike now happily resides back home in St. Louis.

In my previous article, on the Bioscience Labor Market Analysis in St. Louis, I explained the regional economic development complications caused by “overspecialization”, and promised to provide a brief explainer on the issues of economic complexity in general. Here’s why questions of economic complexity are relevant to the St. Louis region.

The Definition of Economic Complexity

Harvard’s Center for International Development (CID) defines economic complexity as:

“A measure of the knowledge in a society as expressed in the products it makes. The economic complexity of a country is calculated based on the diversity of exports a country produces and their ubiquity , or the number of countries able to produce them (and those countries’ complexity).

Countries that are able to sustain a diverse range of productive knowhow, including sophisticated, unique knowhow, are found to be able to produce a wide variety of goods, including complex products that few other countries can make.“

Similar thinking defines the economic complexity for sub-national units, such as provinces, states, and metropolitan areas.

Economic Complexity of Products

However, our interest is in the economic complexity of products. How is this defined? Abon et al (September 2010) define the economic complexity of a product in terms of a weighted average of the incomes of countries producing that product, with the weights related to the countries’ relative comparative advantage.

Another way to think about product complexity is in terms of the information and knowhow needed to produce a given product. Information is more formal, and is generally imparted via a formal education, formal training, documentation, etc.

Knowhow is usually more tacit, and typically refers to the ability to effectively work with other people or, at the firm level, to form the coalitions comprising a business ecosystem. Knowhow makes the information valuable, since it imparts an ability to collaboratively produce things of value that people need (and are typically willing to pay for).

Information Vs Knowhow

Now, a product having high economic complexity typically requires sophisticated information that is not widely available. It also requires that professionals collaborate within firms, and that firms work together in collaborative coalitions.

By contrast, products having low economic complexity typically do not require such extensive and sophisticated information, and can often be produced without as much “working together”. This is not to say that they can be made by a single person, only that we should expect their corresponding producer ecosystem to be less extensive.

Hidalgo (2015), contrasts helicopters and shirts. The former have high product complexity; they require both extensive information and the knowhow to work across coalitions and ecosystems. The latter, by contrast, can be produced using well-defined processes and do not require such extensive collaboration; they are thus of low product complexity.

This matters because increasing a region’s or country’s economic complexity — by making products of high complexity — is associated with increasing incomes and affluence.

Countries whose economic complexity is greater than what we would expect, given their current level of income, tend to grow faster than those that are “too rich” for their current level of economic complexity.

How Relative Economic Complexity Impacts Regional Manufacturing

Thus, a relatively low-labor cost area such as St. Louis could expect to see an increase in incomes and affluence by increasing its economic complexity. Moreover, the evidence correlating increasing economic complexity with rising levels of income and affluence is more compelling than that of several other development measures.

In particular, economic complexity seems to better predict increasing affluence and incomes than years of schooling and other education variables, the availability of domestic credit, the global competitiveness of area firms and industry, and even institutional variables such as the rule of law, political stability, and control of corruption.

It is noted, of course, that all of these no doubt contribute to both economic and product complexity. For example, without the rule of law collaboration between professionals and firms would likely be much more difficult; in addition, the availability of remedies for contract law violations certainly provides an incentive for both individuals and firms to collaborate in the creation of new products.

It is thus a reasonable supposition that diminished economic complexity will likely result in erosion of incomes and affluence relative to other regions. This, however, needs to be formally investigated via future research.

St. Louis Should Embrace Economic Complexity

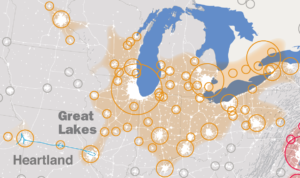

So, as we discussed previously, St. Louis (amongst many other cities) was impacted by the hollowing out of the Great Lakes megaregion. To make our region robust against that happening again, we now need to embrace economic complexity. How we do that is the topic of my final article in this series.