Snapshot of St. Louis Tech Economy and Region

Recently, two research reports have commented on the health of the region’s technology economy. EQ summarizes what they found and offers recommendations that expand upon their findings.

Writing by Mike Fabrizi. Mike Fabrizi was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. An expat for 30 years to the Washington, DC area, he recently retired from a career including long stints with The MITRE Corporation, of McLean, Virginia, and The Aerospace Corporation, of El Segundo, California. Mike’s professional interests include complexity and complex adaptive systems, economic complexity, cities, and regenerative agriculture. He looks for ways to bridge the urban-rural divide, and likes to emphasize that which we share in common, not that which divides us. *Most* people everywhere are good. Give them half a chance and the goodness manifests itself. Mike now happily resides back home in St. Louis.

Recently, two research reports have commented on the health of the region’s technology economy. Both of have caught local media attention. This article summarizes and reviews both publications and offer recommendations that expand upon their findings; if these recommendations are implemented, we believe our community will be strengthened.

- State of the Tech Workforce, published by a trade organization, CompTIA, addresses the IT workforce across many regions, including Missouri and St. Louis.

- Technology 2030, published by a North Carolina concern for the Missouri Chamber of Commerce, is a detailed review and analysis the current state and future direction of Missouri’s technology economy.

Use the table of contents below to jump to the specific section you’re interested in. For a brief summary of the findings, check out this related article:

State of the Tech Workforce

Overview and Caveats

State of the Tech Workforce breaks IT employment into two components:

- Technology professionals who work in technical positions, such as software engineering, IT support, network engineering, data science, etc. These people work in both technology companies and in other industries, such as insurance, health care, retail trade, etc. About 42 percent of the technology professionals work for technology companies, while the remaining 58 percent work in other industries, such as insurance, banking, health care, and retail trade.

- Business professionals who work for technology companies. These professionals have roles such as accounting, sales, finance, HR, advertising, and line management. Approximately 39 percent of net tech employment consists of these business professionals who work in other-than-tech roles.

- N.B. State of the Tech Workforce also includes dedicated, full-time freelancers in its analysis, but excludes part-time gig workers.

Assessment of the St. Louis Tech Workforce

Total IT tech employment in the St. Louis Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSL) grew 0.3 percent from 2021 to 2022. As of April 2022, it stood at 73,485 jobs. The IT tech workforce represents 5.2 percent of the region’s workforce, but has an outsized economic footprint of $13 billion per annum, or 7.1 percent of the “regional economic impact” (we assume the authors meant the regional gross product).

St. Louis’ annual growth rate put it in 45th place among 51 surveyed metro areas, but in 26th place in terms of total IT tech employment.

Other midwestern cities, along with corresponding job growth from 2021 to 2022 and total employment, are detailed in Table 1.

IT Jobs in Select Midwestern Cities, 2021–2022

| City | Job Growth, 2021–2022 | Total Employment |

| Kansas City | 2.1% | 74,404 |

| Indianapolis | 2.1% | 57,055 |

| Nashville | 6.3% | 52,768 |

| Cincinnati | 1.5% | 53,454 |

| Milwaukee | 0.5% | 46,124 |

| Chicago | 1.4% | 245,390 |

| Pittsburgh | 0.0% | 62,469 |

| Detroit | 1.0% | 103,774 |

IT Job Categories in the St. Louis MSA

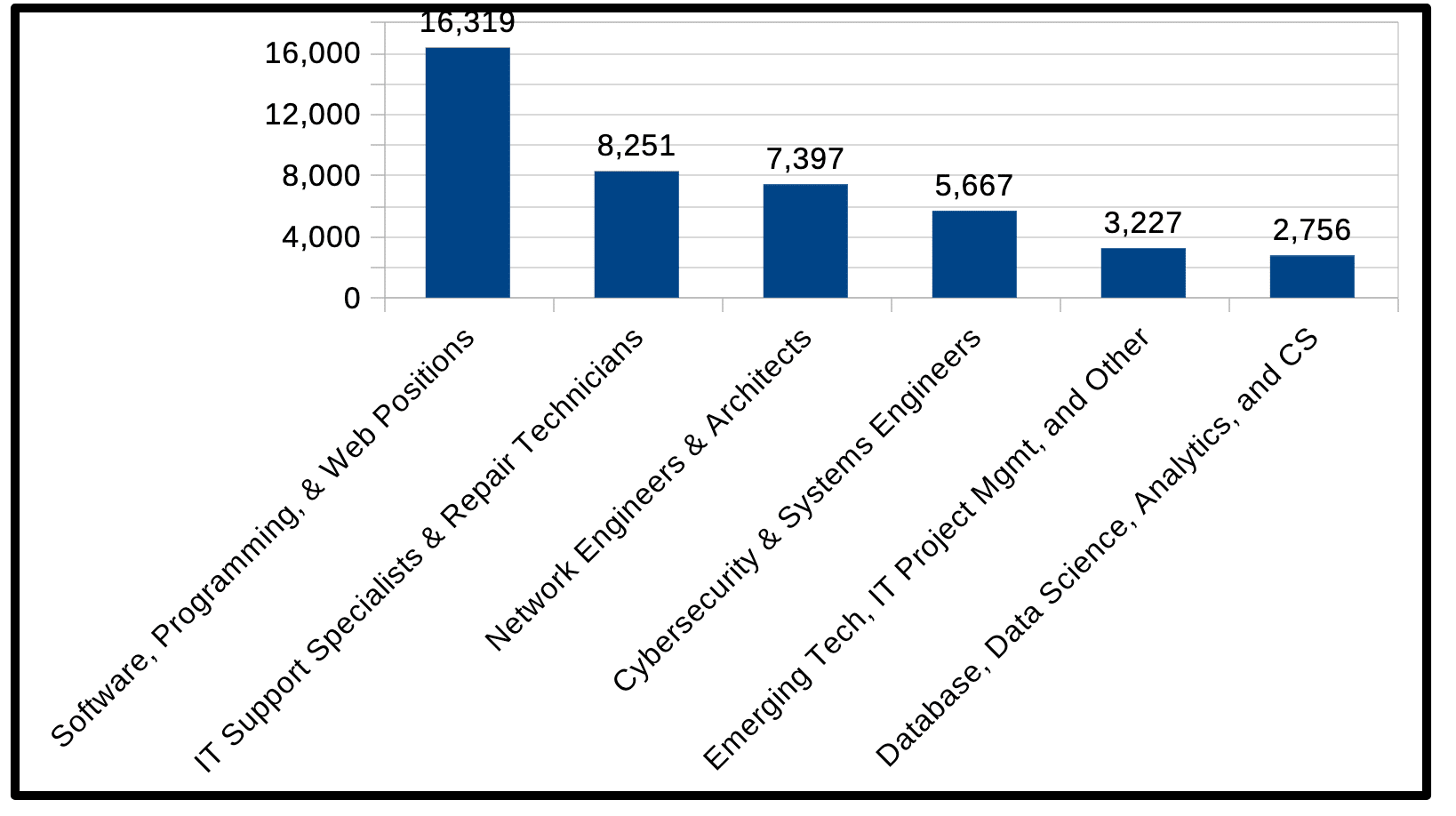

Figure 1 and Table 2, below, represent select IT job categories along with corresponding numbers of jobs in our MSA (the Y-Axis represents number of jobs).

| Job Category | Number of Jobs |

| Software, Programming, & Web Positions | 16,319 |

| IT Support Specialists & Repair Technicians | 8,251 |

| Network Engineers & Architects | 7,397 |

| Cybersecurity & Systems Engineers | 5,667 |

| Emerging Tech, IT Project Management, and Other | 3,227 |

| Database, Data Science, Analytics, and CS | 2,756 |

The median wage for IT tech workers in the St. Louis MSA is $83,545, which is 97 percent higher than the median wages for all jobs in the area. By comparison, St. Louis bioscience workers, according to a 2021 labor market analysis, earn an average of $116,000 per annum.

Another data point offered by the CompTIA report is that state-wide Missouri tech employment grew by about 1.3 percent during this same time, and included 153,419 jobs.

Thus, the picture offered by State of the Tech Workforce is one of lackluster recent IT sector growth. Nonetheless, its generous compensation still equates to an outsized economic impact.

Technology 2030

Overview and Caveats

Technology 2030 is a much more extensive analysis of Missouri’s technology economy. Like State of the Tech Workforce, this report breaks the tech economy into two major components:

- The tech industry, which is comprised of technically-focused companies and which employs both technologists and non-technical occupations, such as accountants; HR, finance and public relations specialists; sales people; and line managers.

- Tech occupations, such as data scientists, software engineers, and biotechnology technicians, who might be employed in tech companies or in other industries, such as insurance, banking, health care, and retail trade.

As in the CompTIA report, the rationale for including the non-technologists who work for technology companies is that these business professionals are instrumental in the delivery of tech products and services. The HR, accounting, and finance professionals who work for technology companies are as vital to the delivery of technology as the software engineers and data scientists who work for these same firms.

Unlike the CompTIA report, however, the Technology 2030 report is not IT focused. Instead, it breaks down the tech economy into four categories:

- Energy Technology, which includes industries related to both fossil fuel and renewable power operations.

- Environmental Technology, which includes industries related to electrification, batteries, environmental consulting, and waste remediation.

- Life Sciences, which includes industries related to pharmaceutical manufacturing and research and development in biotechnology.

- IT, which includes industries related to hardware manufacturing, software development and services, social media, telecommunications, and other computer-related services.

In addition, the report addresses emerging tech, which it describes as difficult to capture in traditional labor market data. Here, it identifies and includes the following newly-emerging industries:

- AgTech, or the application of technologies and sciences such as geospatial, sensors, and advanced bioscience to improve the resilience and productivity of agriculture.

- FinTech, or the application of numerous technologies, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence to banking, finance, and investment.

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy, or the application of numerous technologies to make the use of computer and telecommunication systems more secure.

- Generative Artificial Intelligence, or the use of various algorithms to emulate some aspects of human intelligence, such as the ability to respond to ill-structured questions with human-like, conversational answers.

Finally, Technology 2030 assesses the health of both tech manufacturing and tech services.

Summary of the State of the Tech Economy

Elsewhere in the press, it has been noted that our State’s tech economy growth rate surpassed that of neighboring midwestern states. Arguably, this is akin to saying that the Cardinals stack up well, given that they compete in Major League Baseball’s National League Central Division. Levity aside, Missouri’s tech job force grew 10.6 percent between 2017 and 2022, giving it a rank of 30th in the United States. As a data point, Illinois’ growth rate during this timeframe put it in 37th place.

The report attributes the job growth to net in-migration, especially starting in 2020. Out-migration had exceeded in-migration from 2012 through 2019.

Technology 2030 also attributed the state’s relative success in growing its tech workforce to manufacturing, higher education, venture capital, and a greater concentration of young workers. Other factors cited here and elsewhere include investments in geospatial science, pharmaceutical research and manufacture, AgTech, and advanced manufacturing, as well as a lower cost of housing, which helps to attract workers from more expensive regions.

Missouri’s tech industry was found to have a job multiplier of 2.82, which means that every job created in the tech economy will create, on average, an additional 2.82 jobs elsewhere, such as in services, retail trade, and construction.

Tech workers account for about 6 percent of the State’s total employment, but about 10 percent of gross state product.

Tech industry earnings per worker average $123,300, which is 1.7 times greater than the State average. This figure includes both wages and benefits, such as employer-paid health care and dental insurance and employer contributions to retirement accounts.

Additionally, the State does especially well in tech manufacturing, energy, and environmental tech, as will be detailed below.

Finally, the growing importance of the tech economy in comparison to more traditional drivers of economic vitality, such as trades and services, is noted.

The Good

When we delve into more details, we get a mixed picture. First, some of the good news:

Enterprise Formation

About 370 out of every 100,000 people living in Missouri becomes an entrepreneur at some point in his/her career, putting the state in 17th place (out of the 50 states plus the District of Columbia).

In this author’s view, this entrepreneurialism in part due to the success of and investment in our region’s many innovation districts, with St. Louis and Kansas City each boasting three. (St. Louis’s districts include Cortex, 39 North, and the newer Downtown North Insight District, while those hailing from our cross-state neighbor include the University of Missouri at Kansas City Health Sciences District, the Crossroads Arts District, and the Keystone Innovation District).

Tech Industry Inclusion

The tech industry is not known for being especially inclusive, with the young, white male “techie” stereotype often not far from the truth. However, Missouri has done a better job than most in promoting inclusiveness. The State ranks 6th (again, out of 51) in its “Tech Diversity Index” value, and 12th in women working in tech. This means that we have done a relatively good job of making tech industry employment open to both women and non-Caucasian males.

Kansas City Biologics Manufacturing

Kansas City recently was selected by the US Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Agency as a Tech Hub for vaccine biologics research and manufacture. This will boost that area’s already formidable medical science economy and will likely increase its concentration in life sciences.

(Note: In the parlance of the Technology 2030 report, concentration is assigned a numerical value, with a value exceeding unity signifying over-representation compared with the national average. Such high concentrations often generate an economy’s domestic and international exports and create new wealth. As a data point, Jackson County, home to Kansas City, already has a concentration value of 1.17 in the life sciences category.)

St. Louis Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Investment

St. Louis’ Cortex operates an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API) center, and nurtures research and entrepreneurship in this area. API was designed to deal with critical deficiencies in the American pharmaceutical supply chain, and to prevent the country from being cut off from needed drugs in the event of a health crisis, such as a future pandemic. This author’s view is that this area of investment will only grow in the future. Moreover, that API is a focus area for Cortex will likely increase the St. Louis MSA’s life sciences concentration value.

Ongoing Success of Tech Manufacturing

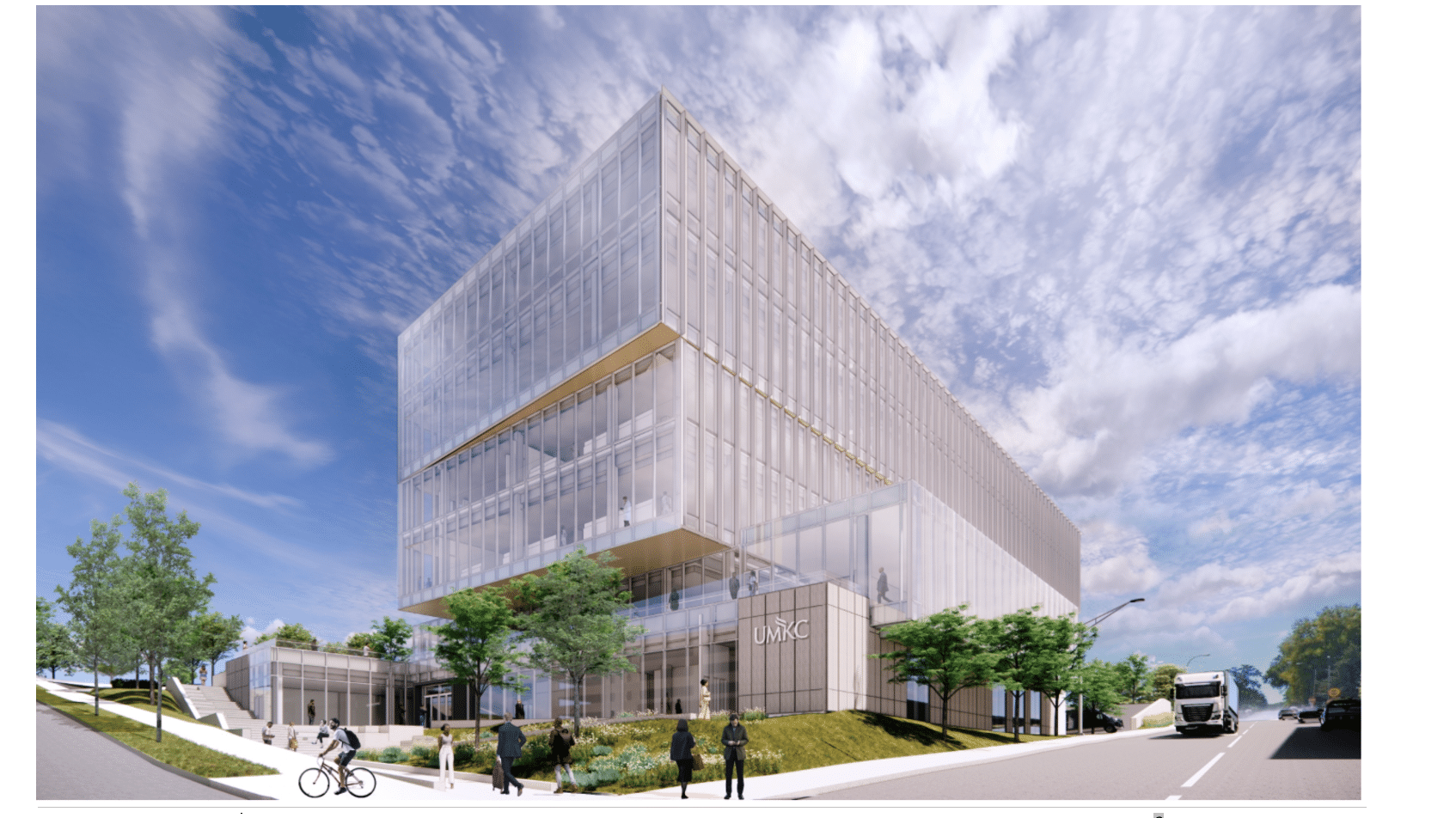

Manufacturing has traditionally been an important part of Missouri’s economy. This is reflected in the tech economy, in which the State was among the top 10 states in tech manufacturing job growth. During the 2017–2022 timeframe, job growth in tech manufacturing was 23.7 percent. This author hastens to add that to support continued growth, area educational and vocational training institutions continue to make investments to prepare the future workforce for manufacturing success. Noteworthy here is the 96,000 square foot, $61 million Advanced Manufacturing Center, which will open on the Florissant Valley campus of the St. Louis Community College system in early 2025.

The Not-So Good

Some negatives and shortfalls noted in Missouri Technology 2030 include:

- Relatively few people entering, or planning to enter, future tech (37th place)

- Relatively low concentration in life sciences (38th place)

- Relatively few people entering, or planning to enter, life sciences (39th and 45th place, respectively)

- Poor rates of internet subscription, broadband access, and affordable broadband (39th, 41st, and 46th place, respectively)

- Poor startup early survival rate (45th place)

- Low rate of STEM eduction completion (47th place)

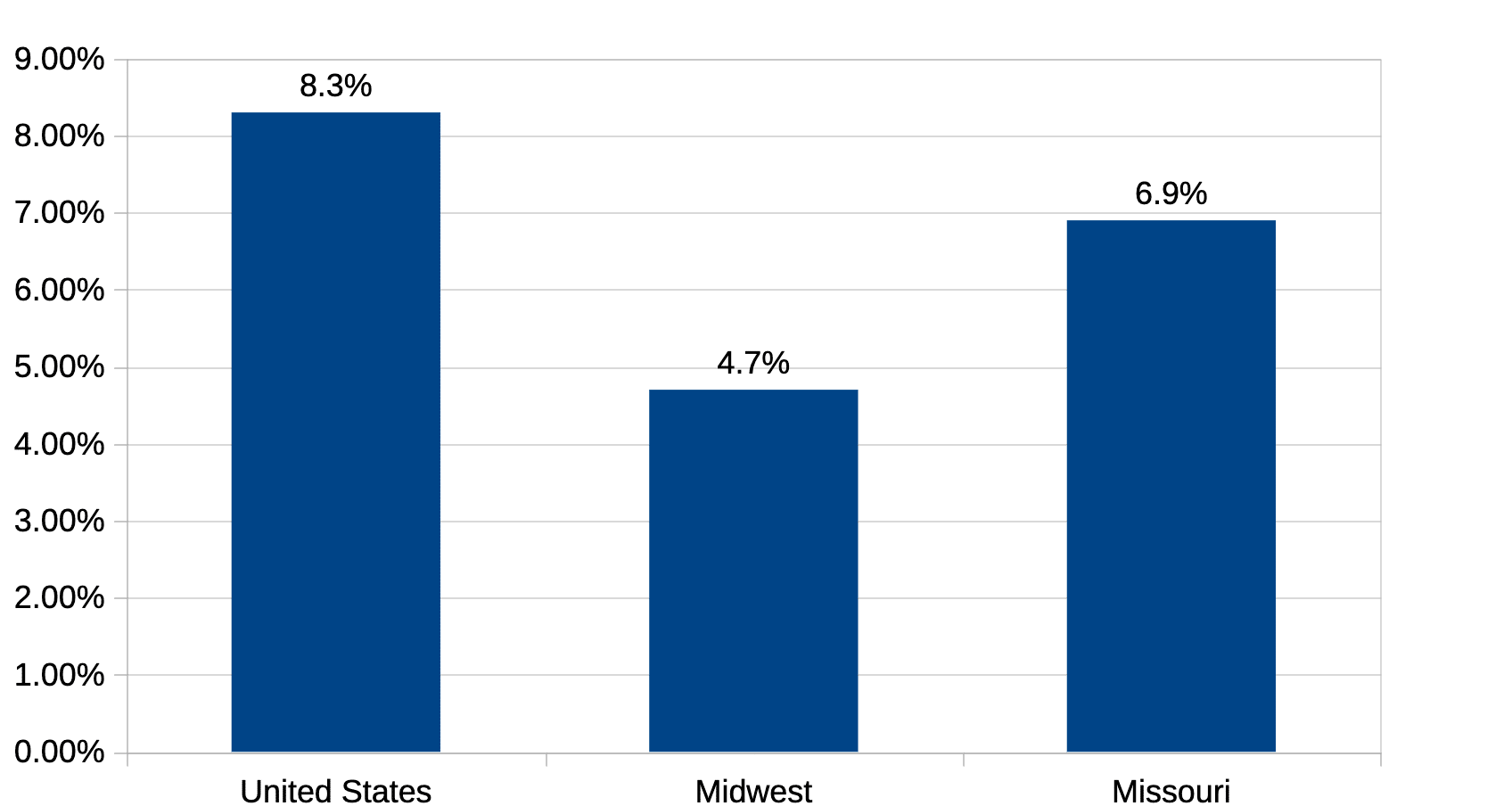

Moreover, tech economy growth was only mediocre in comparison to the national rate of growth, as shown below in Figure 3 and Table 3.

Missouri’s Tech Growth in a National Context

| Region | Percent Growth, 2019–2022 |

| United States | 8.3% |

| Midwest | 4.7% |

| Missouri | 6.9% |

Finally, the various graphics in Technology 2030 paint a mainly-urban picture of tech economy activity, with the greatest concentrations of tech economy work centering on St. Louis and Kansas City, with some dispersion to less urban areas.

Recommendations

Here, we present some recommendations. We believe that implementing these will strengthen our St. Louis and Missouri communities.

Human Capital Formation

Future success in the tech economy will require a trained workforce; given low rates of STEM eduction completion, this is an area in which Missouri clearly needs to improve. One means of such improvement is that of outreach programs to young people, in which the latter are teamed with practicing scientists and technologists and encouraged to pursue STEM careers.

For example, the Jackie Joyner-Kersee Center, in East St. Louis, Illinois, teams young people – many of whom come from underprivileged and underserved minority populations – with Donald Danforth Plant Science Center scientists. This builds the young people’s confidence and makes pursing a STEM career seem less intimidating. More such outreach efforts are sorely needed to shore up this human capital shortfall.

In addition, the presumption that a four-year or graduate degree in a technical field is essential for a STEM career needs to dispelled. STEM careers are also for technicians, who are critically needed as operators and doers – operating critical lab and measurement equipment and performing other tasks for which degrees are not necessary. Junior colleges and vocational training centers have a vital role to play here.

The St. Louis Community College’s investment in advanced manufacturing training has already been mentioned in the foregoing paragraphs. In addition, that same system hosts the Center for Plant and Life Sciences, which trains technicians to provide “skilled hands at the bench”. Their biotechnician training program boasts a job placement rate of over 90 percent. Harris Stowe State University is rolling out a similar training program, but with a geospatial science focus. Graduates of this program could find themselves in demand to service Downtown North Insight District enterprises and the new NGA operations nearby.

Supporting both outreach programs and vocational/technical training programs such as the above is strongly recommended.

Entrepreneur Support

Technology 2030 indicates that Missourians frequently embark upon entrepreneurship, which is good. A vibrant, growing economy needs new ideas and new businesses. Unfortunately, the report also reveals that too many of these new enterprises quickly fail. Hence, a need for entrepreneur support and nurturing is strongly suggested, and is recommended.

There are several means by which to provide this support. The innovation districts offer:

- Laboratory and shared office workspace.

- Greenhouse space, where appropriate.

- Meeting rooms and media services.

- Shared amenities, such as cafeterias, coffee shops, and parking.

- Shared technical services, such as wet and dry labs, cell culture rooms, and a plant phenotyping center.

- Support and coaching both from other entrepreneurs as well as executives from established firms.

- Expert technical advice from academia.

- Legal advice, including protection of intellectual property.

- An introduction to startup finance, including contacts with the seed and venture capital communities.

That said, many new infant enterprises will not be incubated in an innovation district. Thus, other means of support include:

- Entrepreneur Support Organizations (ESOs), such as the recently sunsetted Venture Cafe but also the still extant Lindenwood University Duree Center for Entrepreneurship (DCE) and the Small Business Administration’s IT Entrepreneur Support Network (ITEN).

- Entrepreneur ecosystem builders, such as TechSTL, which foster collaborative and supportive forums in which entrepreneurs find and connect with each other and with potential employees, customers, and information resources.

Yet, many Missourians seem unaware of the entrepreneur support available in the State.

We recommend that these resources be made better known throughout the community, and that they be better supported via grants, philanthropy, and public means.

Startups and new businesses also require ongoing capital and funding infusions to expand and fund operations until they are sufficiently mature to self-fund. The seed and venture capital communities are fairly well known; an introduction to them is usually provided as part of the innovation district nurturing and incubation process.

Yet, for many new Missouri firms, venture capital is simply not appropriate. They will not scale sufficiently to attract a venture capitalist’s interest, or may not wish to cede partial control of their business to outsiders. Alternatives to venture capital include both bootstrapping and commercial lending.

Our recommendation here is information about community banks, which lend mainly to area businesses and people, be more widely disseminated. These institutions are deserving of Missourians’ business and deposits.

Broadband Access in Underserved and Rural Areas

Increased broadband access carries with it the potential to enable people in underserved areas – which are often rural and not adjacent to a major metropolitan area – to more fully participate in the tech economy. This makes these areas more attractive to people who want to work remotely, thus increasing the local tax base. In addition, residents of these hinterlands will be enabled to take advantage of distance learning and training opportunities, thus increasing their employability and making these rural areas more attractive as future locations for major employers.

Finally, increased broadband access creates an even better market for AgTech, which is one of the St. Louis area’s new tech industries, and is also represented in Kansas City’s tech scene. For example, precision agriculture advocates applying interventions – whether chemical or biological – only where and when needed. This type of precision requires data, which is often collected by sensors hosted on drones, satellites, or placed on the ground in farm fields.

But to collect, process, and disseminate data – to transform it into actionable information and put it in the hands of farmers – often requires broadband of some sort. In addition, farmers often require broadband access to do things like download maintenance manuals for farm equipment; many expensive pieces of farm machinery often come without users’ manual, with the owners being provided with a URL for download of a .pdf document. Inability to download this material has actually forced some farmers into using older equipment for which paper technical documentation is more readily available.

Unfortunately, both economics and a regulatory quagmire often preclude rural and underserved broadband deployment. The good news is that the latter, at least, has gotten the attention of agricultural advocacy groups. In response, the American Broadband Deployment Act of 2023 (HR 3557) was introduced into Congress by Representative Buddy Carter (GA-01). If enacted into law, this bill would streamline the broadband deployment approval process and reduce the time required to get broadband to rural customers.

Our Recommendation: At present, deployment requires from several months to several years. Our recommendation here is to work with legislatures, executive branch, public and private universities, and others to advocate for and enable broadband deployment. This is not just a rural issue.

Per the above, rural broadband deployment will help support the growth of one of St. Louis’ and Kansas City’s new industries, that of AgTech. In addition, rural broadband deployment may spread aspects of the tech economy to areas that presently do not benefit as strongly from this new vitality.

Emerging Tech and Core Competencies

Missouri 2030 notes that relatively few people see emerging tech as a career option. Yet, at least some of the emerging tech areas noted in the report are already in strong evidence in our region. Both St. Louis and Kansas City are strongly represented in the AgTech industry.

The former is especially well endowed, with the country’s largest independent plant science organization, the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, serving as an anchor institution to 39 North, an innovation district focused on plant science and AgTech. In addition, as I have previously argued, AgTech builds on St. Louis’ traditional strengths in plant science and agriculture, and is further helped by geography – over 50 percent of the nation’s food, including over 80 percent of the corn and soybean crop, is raised within a 500-mile circle of city borders.

AgTech, plant science, and agriculture are often cited as reasons for agriculture firms to locate in or near St. Louis, and for plant scientists to select our area as a place in which to live. It is one of the region’s core competencies, and a means by which it competes in the global economy. The same is true, though perhaps not quite as strongly, for Kansas City.

Hence, our recommendation here is to continue doing and do more of what we already do so well. Investing resources in our core competencies, corresponding innovation districts, and the larger innovation communities is an investment in our collective future. Moreover, this investment should be broadly focused. In the St. Louis area, for example, increasing the biosciences intellectual capital stock is certainly helped by our world-class Zoo and by the Missouri Botanical Garden.

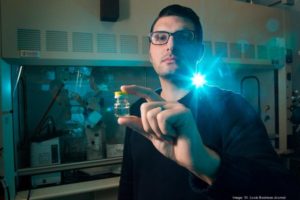

There is another aspect that deserves mention here. An EQ colleague has written about Immunophotonics, an oncology therapeutics startup in the Cortex Innovation District community.

Oversimplifying, Immunophotonics is working on using cancer cells to develop anti-cancer vaccines, which may prevent reoccurrence. These large-molecule drug therapies are sometimes called biologics. Now, St. Louis has long been strong in small-molecule drug discovery. Thus, Immunophotonic’s work will extend this noted strength into an adjacent area, that of biologics.

In the language of economic complexity, movement into adjacent spaces is regarded as a relatively low-risk means for extending core competencies and building new industries. Most of the pieces this new industry requires are already in place, so we are not trying to invent too much that is new. Moreover, all the technology required for this new application is already present, though perhaps deployed in other contexts. Hence, compared with creating something brand new in which the area does not have deep pockets of strength, movement into the adjacent space of biologics is less risky.

Thus, our recommendation is that startups in which movement into adjacent spaces is part of the strategy should receive a priority for funding and support. This will potentially achieve many wins for our region, including:

Support and increase representation in emerging tech.Broadening the area’s economic base, and doing so in a relatively low-risk way.Decreasing the excessive early startup failure rate, since these startups will be lower risk than others and well supported, funded, and nurtured in the innovation districts, our larger innovation ecosystems, and by ample pockets of funding and intellectual capital.

Lethargic IT Sector Growth

State of the Tech Workforce noted a lackluster recent growth rate for the IT workforce. What to do here? First, this may simply be an aberration; Technology 2030, which tabulates the IT sector somewhat differently, noted a similar slowdown in 2021-2022 (0.8 percent growth), but noted a robust growth rate of 12.4 percent during 2017-2022, second only to Environmental Tech’s 13.9 percent. In addition, it is worth reflecting on the jobs listed in Table 2 and Figure 1. Many of these can safely be called IT commodity skills.

They are not the means by which our region competes in the global economy. Rather, they are critical and mid-skill level, but non-core positions pervasive across many industries. Many companies around the world can supply this type of talent. The Indian outsourcing community, especially companies such as Infosys, HCL, Wipro, TCS, and Cognizant have done so for many years.

Our view is that, if our aforementioned recommendations are implemented and Missouri’s tech economy – and the larger general economy – prosper, sufficient demand will be created to reinvigorate IT workforce growth. Thus, this is a problem that may largely self correct. A thriving economy will create ample demand for software engineers, database administrators, cybersecurity staff, and network operations people.

An exception worth noting here pertains to emerging tech, which is noted in State of the Tech Workforce. If this includes high-level skills, for example designing and implementing advanced AI algorithms, then these would not be a commodity skill that can be purchased as needed in the global marketplace.

Still, AI algorithm design and implementation is a skillset that has deep pockets of expertise elsewhere in North America, such as the Vector AI hub near Toronto, Canada as well as in the Bay Area in California. Trying to replicate this algorithm expertise in our area would not be a movement into adjacent spaces (because many of the pieces of the AI jigsaw puzzle are not already present here) and would, therefore, be somewhat high risk.

Another consideration is that AI seems to be an industry in which the first mover advantage is vitally important and difficult to overcome. Missouri, not being an epicenter of early AI development, does not have this first mover advantage. Hence, partnerships and collaboration with other regions might be more sensible than trying to replicate AI as a core competency here.

Thus, in either case, the most sensible approach might be to simply let a prospering and growing tech economy (and general economy) create needed demand for IT skillsets. These skillsets can be grown domestically via the vocational training and community college system, bought in the global marketplace via outsourcing engagements (or -as-a-Service arrangements), or acquired as needed via partnerships and collaboration with think-tanks, academia, and companies from AI innovation hubs.

Hence, our recommendation is to grow the State’s tech economy, per all of the above. Let the tech economy dog wag the IT workforce tail. A second recommendation in this area is to lobby for increased access to the global IT talent pool via measures such as expanded H1B visas, which will permit Missouri and St. Louis employers to hire needed IT talent in the global marketplace.